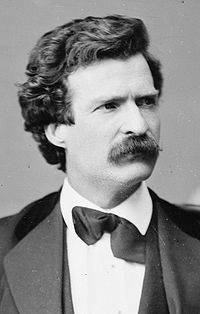

My husband found this excerpt from Mark Twain’s famous criticism of The Deerslayer by James Fenimore Cooper on the blog of Marcel Gagne: Writer and Free Thinker at Large.

My husband found this excerpt from Mark Twain’s famous criticism of The Deerslayer by James Fenimore Cooper on the blog of Marcel Gagne: Writer and Free Thinker at Large.

This excerpt has become known as “Mark Twain’s Rules of Writing.” And I tell you people, verily, these rules are as true today as they were in the nineteenth century.

My personal favorite is:

The personages in a tale shall be alive, except in the case of corpses, and that always the reader shall be able to tell the corpses from the others.

Although I’m also very fond of:

The author must say what they are proposing to say, not merely come near it.

My husband followed Marcel’s link to Project Gutenberg, where Twain’s entire criticism of The Deerslayer is housed, and he sent me this excerpt on the definition of art, which it seems to me we need in this era now more than ever:

“There have been daring people in the world who claimed that Cooper could write English, but they are all dead now—all dead but Lounsbury. I don’t remember that Lounsbury makes the claim in so many words, still he makes it, for he says that Deerslayer is a “pure work of art.” Pure, in that connection, means faultless—faultless in all details—and language is a detail. If Mr. Lounsbury had only compared Cooper’s English with the English which he writes himself—but it is plain that he didn’t; and so it is likely that he imagines until this day that Cooper’s is as clean and compact as his own. Now I feel sure, deep down in my heart, that Cooper wrote about the poorest English that exists in our language, and that the English of Deerslayer is the very worst that even Cooper ever wrote.

“I may be mistaken, but it does seem to me that Deerslayer is not a work of art in any sense; it does seem to me that it is destitute of every detail that goes to the making of a work of art; in truth, it seems to me that Deerslayer is just simply a literary delirium tremens.

“A work of art? It has no invention; it has no order, system, sequence, or result; it has no lifelikeness, no thrill, no stir, no seeming of reality; its characters are confusedly drawn, and by their acts and words they prove that they are not the sort of people the author claims that they are; its humor is pathetic; its pathos is funny; its conversations are—oh! indescribable; its love-scenes odious; its English a crime against the language.

“Counting these out, what is left is Art. I think we must all admit that.”

—Mark Twain